THCS Handbook for Transferring and Implementing Health and Care Solutions

The THCS Transferability and Implementation Framework supports and promotes the transfer and implementation of health and care solutions across the countries, regions, and organisations. The framework:

- Helps to understand what transferring and implementing is about.

- Provides means for describing health and care solutions to facilitate their adoption in other health and care systems.

- Offers guidance on how to perform the various tasks involved in transferring and implementing solutions developed elsewhere,

- Highlights the key tasks necessary for transferring and implementing solutions.

- Focuses principally on complex solutions

- Is aimed at those who manage, coordinate, plan, and perform transfer and implementation activities in health and care organisations as part of programs, projects, and everyday practices.

Introduction

Health and care systems across Europe face similar challenges: aging populations, rising chronic diseases, growing health and social needs, and tight budgets. Instead of reinventing the wheel, sharing and adapting evidence-informed solutions can save time, cut costs, and improve care.

The THCS Transferability and Implementation Framework helps speed up the adoption of evidence-informed solutions—like treatments, services, processes, and policies—by adapting them to new settings. Since what works in one place may not work everywhere, the framework supports identifying and adapting existing solutions to local needs. Creating new solutions should only happen when no suitable option already exists.

The framework mainly focuses on complex health and care solutions—those that combine many different actors, elements, and interactions to improve care. These solutions need careful coordination, flexible strategies, and ongoing updates to stay effective, as they must manage many connected factors that impact patient and client outcomes and care quality. Still, the framework can be used for simpler solutions too.

This framework is designed for professionals involved in managing, planning, or delivering health and care services in projects, programs, or daily operations.

What is transferring and implementing about?

Transferability and implementation can be understood based on the following starting points and assumptions:

- Transferring and implementing is an iterative process.

- Solutions are studied as practices.

- Evidence is relational.

- Evaluation is theory-based.

Iterative Transfer and Implementation Process

An iterative approach to transferring and implementing solutions emphasises that the process does not start from a fixed starting point, for example from research and proceed linearly to implementation. It involves diverse stakeholders—such as practitioners, management, policymakers, patients, and researchers—throughout the entire process, ensuring a dynamic and adaptive approach to achieving sustainable change. Research is an integral part of the process, not a separate phase.

This feedback-driven approach allows research, development, testing, and experimentation to happen simultaneously. It enables a rapid response to emerging issues and treats implementation as a continuous priority. Collaboration among stakeholders is essential, as implementation is an organisational transformation and learning process. Additionally, the process itself helps generate evidence on what works and how to adapt solutions effectively in different contexts.

Solutions as Practices

A practice-based approach views solutions in health and care as recurring practices with specific purposes, such as preventing health deterioration, promoting healthy lifestyles, improving treatment adherence, or reducing hospital readmissions. Solutions are continuously enacted and maintained through practices.

Health and care practices are shaped not only by people but also by tools, technologies, and environments. This socio-material perspective shows that practice and context are deeply connected—you cannot fully separate them.

Recognizing socio-materiality is key to designing, improving, and transferring solutions. It encourages care providers, managers, policymakers, and researchers to consider both human and material factors when shaping practices. By addressing these together, we can enhance care quality, safety, and system performance. Practices also sustain the wider health and care system through their ongoing interactions.

Relational Evidence

Effectiveness in health and care is not universal or entirely tied to a specific setting—it is relational. A solution can achieve similar outcomes in different contexts if its core elements and interactions are properly adapted. But especially for complex solutions, results may still vary due to local differences in relationships, interactions, and environments.

Solutions do not work in isolation; they interact with people, tools, and systems in their setting. Their effects emerge from these relationships. Understanding a solution’s key activities, interactions, and essential components helps determine what must stay the same to maintain effectiveness, and what can be adapted to fit the local context. The function must be preserved, but the form can change.

Often, knowledge of the original solution is limited. Breaking it down theoretically helps identify what’s critical. Evidence of effectiveness should come from real-world settings, valuing practical insights over controlled conditions. This approach captures the complexity of implementation across diverse contexts.

Instead of following a rigid hierarchy of evaluation methods, the relational approach tailors methods to fit the practice being evaluated. The goal is to close the gap between research and practice, enabling well-informed, person-centred, and context-sensitive decisions in health and care.

Theory of Change

A theory of change explains how an intended purpose can be achieved by mobilising the core human and non-human elements, interactions, and features of a solution and its context. It includes the purpose, target group, and hypotheses on how the purpose will be realized and achieved by engaging the necessary, activities, interactions, and elements in the practice.

Initially developed within the solution’s original setting, the theory starts broad and evolves as the solution is tested in new environments. It serves as a tool for sharing, adapting, testing, and implementing a solution across different systems and contexts. Each implementation provides insights into what works, what needs adapting, and how well the solution transfers across contexts.

With each iteration, the theory of change is refined—capturing lessons, adjustments, and improvements to guide future action.

How to do it – when transferring and implementing?

The THCS framework suggests a set of principles to perform the diverse tasks of transferring and implementing health and care solutions to achieve sustainable change. These principles guide and are being enacted through the entire process from challenge to sustainable change:

- Demand-Based Development

- Person-centred Development

- Co-Creation

- Mutual Learning

- Openness and Transparency

- Agility

- Evidence Generation

Demand-Based Development

Transfer and implementation activities are driven by demand. The efforts, goals, and objects of these activities are guided, shaped, and negotiated by considering the specific demands, needs, and preferences of patients / clients, health professionals, managers and administrators, and other actors and stakeholders.

Person-Centred Development

Person-centred development of care places the problems, needs, preferences, values and goals of patients, clients, and citizens at the forefront of development processes. It involves designing, adapting, and implementing solutions with a primary focus on improving the overall experience and outcomes for the individuals receiving care. This approach recognizes that patients and clients are not just passive recipients of health and care services but active developers of them and participants in their own care.

Co-Creation

The co-creation approach emphasises the active involvement of all stakeholders—such as health and care professionals, management, policymakers, patients and clients, and researchers—throughout the entire process of transferring and implementing a solution. Each stakeholder brings a unique perspective, helping to shape both the challenge and the solution.

Implementation is complex and influenced by cultural, societal, and contextual factors. Co-creation ensures that multiple viewpoints are considered, as differences in values, norms, and expectations can affect how well a solution is accepted and integrated into a new setting.

A multidisciplinary core team is essential for leading the development process. This team must be of a manageable size, capable of agile decision-making, and maintain clear communication and shared responsibilities. Team composition can be adjusted as needed. Additionally, other stakeholders with diverse perspectives should be engaged in specific tasks to ensure the solution’s success.

Mutual Learning

Mutual learning should be enabled throughout the transfer and implementation process. In mutual learning, several actors and stakeholders engage in a collaborative and reciprocal exchange of knowledge, skills, and experiences whilst working on shared solutions and goals.

This form of learning occurs through interaction and dialogue where each participant has an opportunity to gain experience from the others. There is mutual learning within and between systems when transferring a solution from a system to another. Mutual learning supports continuous improvement and adaptation of solutions by integrating insights from various actors, ensuring solutions are better tailored to local needs.

Openness and transparency

Open innovation emphasises collaboration, knowledge sharing, and integration of external ideas and resources into development activity. Open innovation encourages sharing information on development activities, the developed solution, and the evidence of effectiveness, to promote the transfer and implementation of knowledge across the systems.

Transfer of solutions across the systems is possible only if this kind of knowledge is shared. Transparent processes facilitate information exchange across countries, regions and organisations, and between various health and care providers, enhancing the effectiveness of transferred solutions and fostering mutual trust among stakeholders.

Agility

An agile development approach is characterized by flexibility, adaptability, and a focus on delivering value quickly and efficiently. Agile development responds to the need for organisations to be more responsive and adaptive in a rapidly changing environment. It ensures that solutions remain relevant and effective in a dynamic environment, allowing for continuous improvement based on feedback and emerging challenges.

Development activities are broken into smaller manageable iterations that allow for regular reassessment and adaptation based on feedback and changing requirements. The approach calls for creating a minimum viable solution, which allows for quick development and testing sprints. However, agile development is not always possible due to distinct reasons, such as patient safety, ethical considerations, or complexity.

Evidence Generation

There are significant gaps in evidence regarding how effectively health and care solutions improve access, quality, outcomes, and overall effectiveness across different contexts, care settings, and populations. Additionally, there is limited knowledge on how to scale and spread these solutions.

By adopting a "learning while implementing" approach, evidence can be generated through continuous evaluation of improvements and transformations. This ensures that solutions are informed by real-world data and ongoing feedback, allowing for their refinement and adaptation to better fit local needs.

What to do – when transferring and implementing?

The THCS framework suggests key tasks to perform (what to do) when transferring and implementing a solution developed elsewhere, aiming to achieve sustainable change. The process is not a linear and strict step by step; instead, you iterate between the diverse tasks until the entire process is finished, and sustainable change achieved. There is no right order for performing the different tasks.

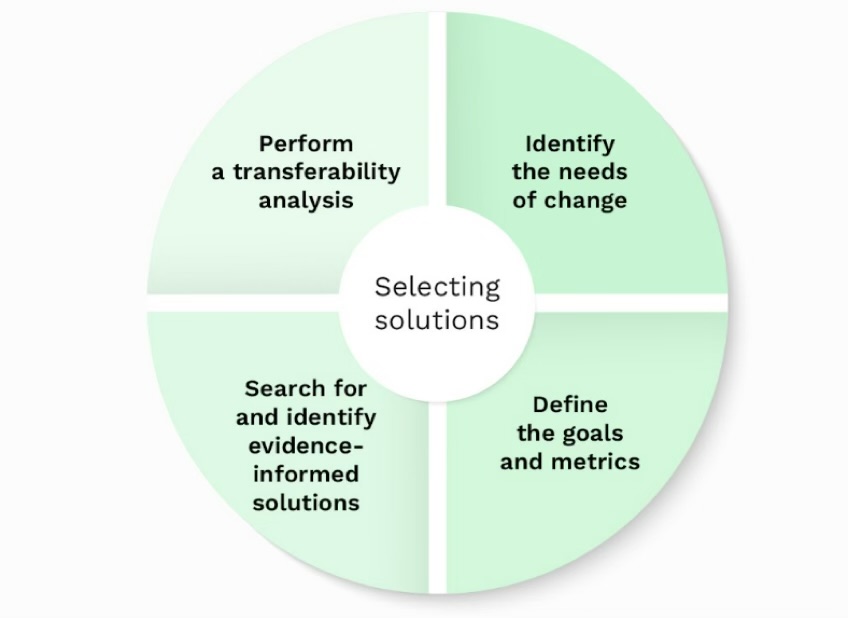

The key development tasks can be grouped in four interconnected sets:

- Describing Health and Care Solutions

- Aligning and Organising Development Activity

- Adapting a Solution Developed elsewhere

- Implementing the Adapted Solution

To enhance openness, transparency, and transfer of solutions, THCS provides the Knowledge Hub as an online platform for describing health and care solutions and their evaluation results and sharing them with potential adopters.

Describing Health and Care Solutions

Successful adoption of a health and care solution in different contexts depends on how well the original developers and adopters have documented its theory of achieving change, implementation process, and evaluation outcomes. A well-structured description supports communication, adaptation, and scaling across different settings.

The following contents are essential for describing any type of health and care solution, for example treatments, services, workflows, policies, service delivery models, and knowledge management:

- Name of the solution

- Purpose

- Target group

- Core Actors, Elements, Interactions, and Features to Achieve the Intended Outcomes

- Key Organisational and Broader Context features for Success

- Evaluation Knowledge of Implementation (see the section Implementing the solution)

- Evaluation Knowledge of the Outcomes Achieved with the Solution (see the section Implementing the solution)

When developing a novel solution or adapting a solution developed elsewhere, it is useful starting to describe the solution early in the process. This way, it can be communicated within your own organisation and to its adopters in other contexts and settings. The description can be improved and refined when needed during the development process based on the testing and evaluation.

The description of a solution in the THCS knowledge Hub consists of three sections:

1) Describing the Solution (Theory of Change)

2) Describing the Implementation Evaluation of the Solution (see the section Implementing the solution)

3) Describing the Outcome Evaluation of the Solution (see the section Implementing the solution)

Click here to see AI-generated examples of theories of change of health and care solutions.

Describe the solution you developed and its implementation and outcome evaluation or the implementation and outcome evaluation of the solution you adapted here.

Explore other description templates in the tools section here.

Aligning and organising development activity

The THCS framework outlines key tasks for aligning and organising development activities to achieve sustainable change. There is no right starting point for how development activities should begin in an organisation. In some cases, new technologies, models, or solutions may present opportunities for change, leading to the launch of development efforts even without a clearly defined challenge or problem. However, even in such cases, it is essential to perform the tasks recommended by the THCS framework to ensure effective implementation and meaningful outcomes.

Identify the Needs of Change

The impulse for development in a health and care organisation can arise from various sources, such as poor service outcomes, rising costs, limited access to care, inefficiencies in work processes, growing health and social challenges, or changes in laws and regulations. A situation is not inherently a problem or challenge but is defined as one based on context and perspective.

To address a challenge, it is essential to study the current situation by gathering and analysing both quantitative and qualitative data. The depth of this analysis depends on the specific issue being examined, and it should provide a baseline understanding of the system in relation to the challenge.

Since different stakeholders may have diverse, conflicting, and evolving needs, their perspectives must be negotiated and translated into a shared starting point for development. Achieving consensus on the needs – which is often difficult – ensures that the solutions are aligned with the actual requirements of the health and care system, creating a solid foundation for meaningful and sustainable change. This may require reconciling differing needs and bringing together varying expectations.

Supporting Questions:

- What data or evidence is available to study the challenge, and what additional information is needed?

- How does the challenge interact with other ongoing initiatives or systemic issues in the health and care system?

- Who are the key stakeholders related to the challenge?

- How do they perceive and define the main challenge?

- How does the challenge impact them?

- What specific needs or expectations do they articulate?

Define the Goals and Metrics

Translate the needs into shared outcome goals. This process is not a rigid and mechanical procedure, but rather a negotiation process where the shared goals are established. These goals serve as criteria for searching for and finding evidence-informed solutions. Outcome goals define the outcomes to achieve through the solution. Outcome goals can be categorized into short-term and long-term objectives, though the distinction between them is not clear-cut.

Short-term outcome refers to an immediate or near-term outcome that occurs as a consequence of implementing a solution. These outcomes are typically measurable within a relatively short timeframe, and they act as stepping stones toward achieving longer-term goals. Examples of short-term outcomes are increased patient engagement, changed behaviour, patient satisfaction, reduction in emergency visits, and reduction in unnecessary hospital admissions through early intervention.

Long-term outcome refers to the sustained outcome achieved over an extended period. These outcomes represent the ultimate goals of a solution, and often indicate meaningful changes in health, behaviour, quality of life, or societal conditions. Examples of long-term outcomes are improved health, savings in healthcare costs, reduction in suicide rates, decrease in diabetes-related amputations, and reduction in obesity rates among adolescents.

In addition to the goals, define the outcome metrics and indicators for following and evaluating the achievement of the goals. You need these metrics and indicators throughout the process. Update the goals and metrics when needed.

Supporting questions:

- What specific goals do we want to achieve based on stakeholder needs?

- How can these goals be framed to be measurable and actionable?

- In what ways do these goals align with broader organisational or policy objectives?

- What key metrics and indicators can be used to effectively measure progress?

- What qualitative and quantitative data will provide meaningful insights?

- How often should these metrics be reviewed and adjusted?

Search for and Identify Evidence-Informed Solutions

There is a high probability that a solution already exists that has been tested and meets your needs, with evidence of achieved outcomes and information of how to get it to work. The challenge lies in identifying these solutions. To achieve your goals, search for evidence-informed solutions developed elsewhere, using criteria based on your goals.

This approach directs resources toward proven solutions, increasing the chances of successful implementation. Identify potential options from sources such as the THCS Knowledge Hub, “good practice” databases, articles, reviews, practice guidelines, and other organisations or systems.

Supporting questions:

- How have other organisations successfully tackled similar challenges?

- What existing solutions have been implemented in similar health and care settings?

- What emerging solution and innovations could address these needs?

Perform a Transferability Analysis

After identifying potential solutions, perform a transferability analysis to assess whether they can be effectively adapted to your health and care system or population. This process assesses the differences between the heath and care system requirements for enabling the solution to work and your own system, ensuring its applicability and effectiveness beyond its initial context.

Transferability analysis is the process of assessing whether a solution developed in one context can achieve similar outcomes when applied to a different context. Simple solutions are more likely to be successfully transferred and yield comparable results, whereas complex solutions may face challenges in achieving similar outcomes due to their intricate dependencies and interactions. Transferability analyses assess the applicability of the solution and the possibility of achieving similar outcomes in another context as in the original context. However, it is important to note that some solutions may be applicable but may not achieve the same outcomes.

Transferability analysis is crucial for evidence-informed decision-making in health and care, as it helps to avoid the uncritical application of solutions that may not be suitable in a different context. It also contributes to more effective and efficient health and care service delivery and policy development by considering the nuances and specific requirements of diverse patient populations and health and care systems.

Transferability analysis is conducted before and after the implementation process. Before making the transfer decision, the focus is on anticipated transferability. After the solution is transferred, the focus shifts on how the outcomes were achieved and whether the context changed them.

THCS transferability analysis tool

THCS Transferability Analysis Tool is available in the THCS Knowledge Hub (link). The tool is meant for assessing the transferability before making the decision of transferring a solution.

THCS transferability analysis looks at the broader context, including cultural, economic, and health care system factors that might influence the success of transferring a solution and achieving the expected outcomes.

The THCS transferability analysis is thematised according to PIET-T model into four categories:

- Solution – Assess the clarity and quality of the description of the solution

- Population – Compare the population / target group of the solution to your population / target group and assess if the differences would affect achieving the outcomes

- Environment - Compare the key environmental requirements of the solution to your context and assess if the differences would affect achieving the outcomes

- Transfer – Assess the support for transfer and implementation

The transferability analysis is performed based on the knowledge and information available about the core actors, elements, interactions, and features of the original solution and the contextual requirements and enablers needed to get it work, about the evaluation of its implementation, and about the evidence of the achieved outcomes.

The THCS Transferability Analysis Tool includes open fields following each sub-question. These fields provide space to elaborate on potential adaptations to the solution and / or to the context or describe implementation strategies that would help overcoming other identified obstacles.

It depends on the type of solution you are adopting who are the relevant stakeholders to involve in the team for performing the analysis and which ones of the aspects are relevant, and which are irrelevant. The assessment of the different aspects in the transferability analysis (link below) supports decision-making, but it is not alone enough to make the needed decisions concerning the transfer and adoption of a solution.

Perform a transferability analysis on every solution in your list by downloading an assessment form here.

Explore other tools for performing transferability analysis in the tools section here.

Click here to see AI-generated examples of aligning and organising development activity.

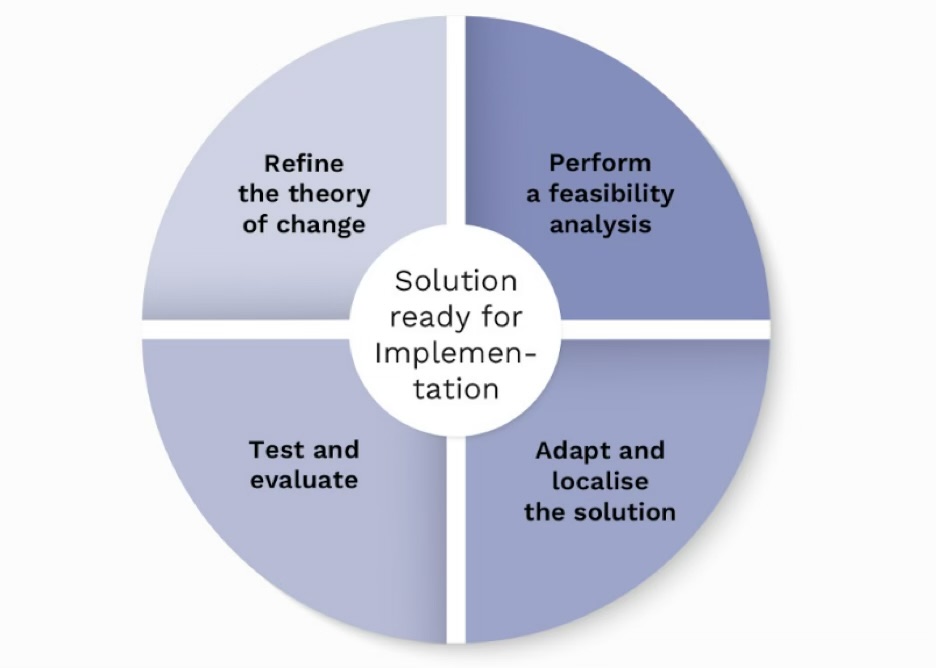

Adapting a solution developed elsewhere

In health and care, adaptation of a solution from one setting to another refers to the modification or adjustment of a health and care solution when moving it from one health and care context to another, but also modifications in the adopting context.

This process recognizes that what works effectively in one health and care setting may not be directly applicable or appropriate in another due to variations in patient populations, staffing, technology, workflow, and other resources or factors. Therefore, adaptation is essential to ensure the successful implementation of a solution in a new health and care context.

Enabling the participation and engagement of the local health and care providers, administrators, and community stakeholders in the adaptation process is necessary, as they have a deep understanding of the local context and can provide valuable insights. However, successful implementation does not guarantee that you will achieve similar outcomes with the solutions as was achieved in the original context. This is due to differences in any kind of element and interaction of the adapted solution and / or its context compared to the original solution.

Adapting a solution consists of four interactive and iterative key tasks:

- Perform a Feasibility Analysis.

- Adapt and Localise the Solution.

- Test and Evaluate

- Refine the Theory of Change.

Iterate between the tasks until all the involved agree that no further improvements can be made to the solution and its context.

Perform a Feasibility Analysis

Feasibility analysis is a means to support the adaptation process. Feasibility analysis refers to the systematic assessment of whether a solution is practical, viable, and achievable within a specific health and care setting. It involves assessing several aspects to determine whether the intended solution can be successfully implemented and sustained. Feasibility is synonymous to applicability which focuses on whether the solution can be implemented in a local setting

The feasibility analysis is a critical step in health and care planning and decision-making to ensure that resources are allocated efficiently, and that the solution produces the expected and desired outcomes. The assessment of the different aspects in the feasibility analysis (see the tool below) supports decision-making, but it is not alone enough to make the needed decisions concerning the feasibility of a solution.

A feasibility analysis is essential to minimize the risks associated with health and care initiatives, prevent wasted resources, and increase the likelihood of success. It provides decision-makers with the information needed to make informed choices about whether to proceed with a solution. Successful feasibility analysis contributes to more efficient and effective health and care service delivery and resource allocation.

THCS feasibility analysis tool

THCS Feasibility Analysis Tool (link) focuses on whether a solution can be successfully implemented within a specific setting. The tool includes eight aspects that are formed and thematised in the THCS partnership and supplemented with aspects from the Structured Assessment of FEasibility (SAFE) framework and aspects from other literature.

Each aspect includes sub-questions followed by open fields. These fields provide space to elaborate on potential adaptations to the solution and/or to the context or describe implementation strategies that would help overcoming other identified obstacles.

A feasibility analysis can be performed before, during, and after the testing / piloting of a solution. It depends on the type of solution you are adopting who are the relevant stakeholders to involve in the team for performing the analysis and which ones of the assessment aspects are relevant and which ones irrelevant. The shared discussion will help recognizing different dimensions and improves reasoning.

Assess with the help of the tool whether an adaptation is needed in the solution and / or in your organisational setting to implement the solution. Adaptation can concern any kind of human or non-human element needed for the solution. Adaptation can, for example, be made to improve cultural compatibility or to address a new client group.

After the first feasibility analysis, decide with which solution or solutions you proceed to testing / piloting. Perform the feasibility analysis again during and after the testing if needed and decide whether to implement a solution. Only start to develop a novel solution if the feasibility analysis does not support to proceed with any of the solutions.

Perform a feasibility analysis on each of the solutions on your list by downloading an assessment form here.

Explore other tools for performing feasibility analysis in the tools section here.

Adapt and Localise the Solution

When adapting and localising a solution developed elsewhere, the goal is to achieve a viable local solution and sustainable change. After performing the first feasibility analysis your understanding of how to adapt and localise the solution in your setting has increased.

Design a minimally viable solution based on the original solution and on the feasibility analysis to achieve your goals. Ensure your solution includes the core actors, elements, interactions, and features of the original solution and the contextual elements needed.

Consider whether modifications or adaptations to the original solution are necessary to align with your setting's unique characteristics and needs. This may involve modifying certain elements of the solution and / or some contextual elements.

Be aware that when localising and adapting a given solution some contextual elements may have to be changed to ensure the solution works, not only adapt the solution to the organisation.

Supporting questions:

- What are the essential elements and interactions within the original solution that must be maintained to preserve the solution’s success and effectiveness?

- What are the specific actors, elements, interactions, and dynamics unique to your setting, and how do they differ from those of the original solution?

- What modifications or adaptations to the original solution are necessary to align with your local setting's unique characteristics and needs?

- What modifications or reconfigurations are necessary in your context to support the integration and effectiveness of the original solution?

Test and Evaluate

Testing and evaluating a prototype in health and care refers to the systematic process of evaluating and analysing a preliminary or early version of a solution to determine its feasibility, usability, and effectiveness. Testing allows for any necessary adjustments to be made before full implementation, thereby increasing solution's overall success and acceptance. Testing is crucial in the development of a novel solution to ensure that the final health and care solution meets the local needs and intended goals.

Existing evidence-informed solutions have already been tested and evaluated, and therefore the process of implementing them might be faster, more straightforward, and more cost-effective than developing a novel solution. When adapting a solution developed elsewhere, the need for the extent of testing depends on what kind of solution is in question and how much it has been tailored and modified from the original version.

When testing the solution, you test how the original or modified theory of change works in your context. Plan the testing and evaluation of your minimally viable solution. Test the solution as rapid testing sprints if possible. Evaluate the solution by using the outcome metrics you defined earlier when aligning and organising the development activity. Adapt and repair the solution based on the evaluation results. The sprints continue iteratively until all the involved agree that no further improvements can be made to the solution.

Supporting questions:

- What reconfigurations in the solution are needed based on testing results, and how can these changes be iteratively refined to stabilize the solution?

- How does your context differ from the original, and what specific adaptations are needed to align the relationships, roles, and interactions to successfully integrate the solution?

Refine the Theory of Change

The original theory of change works as a baseline theory for testing and evaluating a solution in a new context. Refining a theory of change is a dynamic process that involves iterative learning and adaptation based on insights gained from testing and evaluation. It is about listening to data, responding to context-specific insights, and staying flexible to ensure the solution achieves its intended outcomes. This iterative refinement improves both the effectiveness and adaptability of the solution over time.

Supporting questions:

- What tools, data sources, or feedback mechanisms are most useful for refining the theory of change in this specific context?

- What key challenges or opportunities have been identified during the testing phase, and how can they guide adjustments to the solution?

Click here to see AI-generated examples of adapting a solution developed elsewhere.

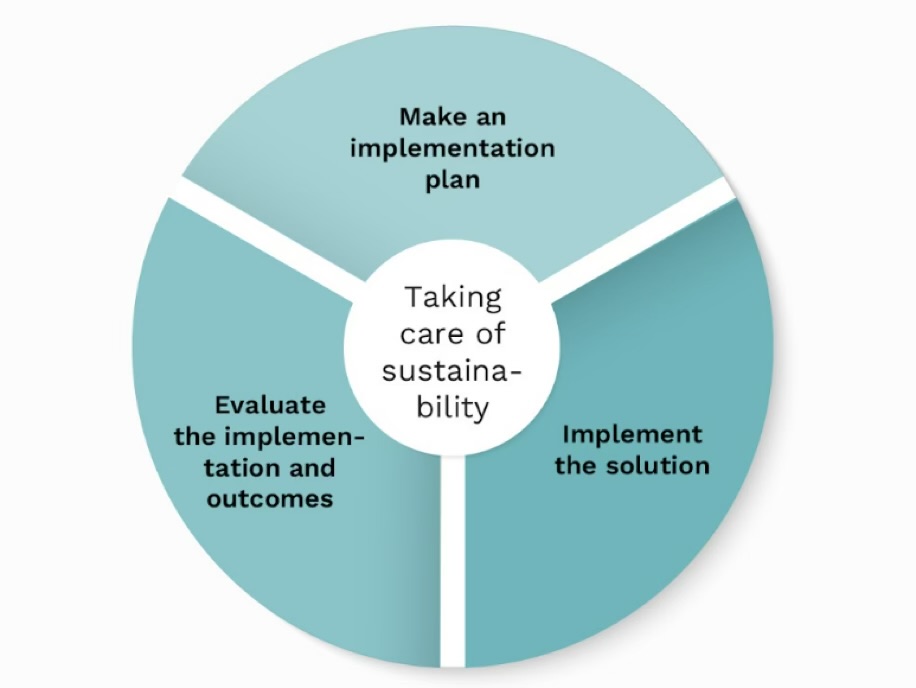

Implementing the solution

Implementation of a solution in health and care refers to the process of putting a proposed solution into action within a health and care setting and it becoming a routine practice. This process involves translating the knowledge and information about a solution into real-world practice with the aim of achieving defined outcome goals.

Implementing a solution consists of three interactive and iterative key tasks:

- Make an Implementation Plan

- Implement the Solution

- Evaluate the Implementation and Outcomes

Make an Implementation Plan

After testing and achieving consensus on the adapted solution, prepare a plan to implement the solution in your organisation. A structured implementation plan ensures that all necessary resources, timelines, and responsibilities are clearly defined, enhancing the solution’s chances of success.

Create an implementation team early in the transfer process to the different sites where the solution will be implemented. This team will be responsible for the implementation and the strategies to get people change their current ways of working. Involve the “relevant” actors and stakeholders in the implementation team in relation to the solution you are going to implement.

An implementation plan for a solution should be comprehensive and well-structured to ensure the successful deployment of the solution. It is a dynamic document that may need adjustments as the implementation progresses. Start preparing the plan with the team in the beginning of the transfer process. Regularly review and update the plan to ensure it aligns with the evolving needs and circumstances of the implementation. Communication and collaboration among stakeholders are key to successful implementation.

Use the checklist here for preparing an implementation plan.

Explore other checklists for preparing an implementation plan in the tools section here.

Implement the Solution

Perform the implementation process according to the plan. Ensure that the core elements, interactions, and features of the solution and its context are enacted. Ensure that staff gets the support they need to successfully implement the solution.

Evaluate the Implementation and Outcomes

Monitor and evaluate the implementation process. Use the metrics defined in the implementation plan for evaluating the success of the implementation. This evaluation can report, for example,

the successes, challenges and barriers in the process. Adapt and repair the process when needed.

Evaluate the achievement of the short- and long-term outcome goals which you defined when organising the development activity. These are useful to perform after an appropriate time from the implementation has passed.

Take care of Sustainability

Sustaining the adapted solution involves ongoing efforts to support, update, and refine the adapted solution over time. Health and care environments are dynamic, and changes may be necessary due to evolving practices, technological advancements, regulatory requirements, or shifts in patient demographics. It is not just about maintaining the status quo but also continually improving and optimizing the adapted solution. This may involve leveraging data analytics, feedback from users, and incorporating advancements in technology to enhance efficiency, effectiveness, and overall performance.

Involving a range of stakeholders from the start of the process maximises the likelihood of long-term sustainable implementation. Hence, developing capacity, forming plans for implementation and maintenance, and identifying dedicated resources for maintenance will be a focus of these processes. Plans for long-term maintenance will ideally be developed incrementally through adaptation, testing, and evaluation. As context changes over time, the process of making responsive adaptations will continue after solutions are taken to scale.

Supporting Questions:

- What mechanisms can be established to continuously gather and integrate feedback from various stakeholders (e.g., patients, staff, administrators) into the solution's maintenance and improvement processes?

- How can evolving associations among actors, such as technological tools and regulatory bodies, be managed to ensure the solution remains effective and aligned with its intended outcomes?

- What dedicated resources (e.g., funding, training, technical support) need to be mobilized to sustain the solution’s capacity to adapt and evolve over time?

Click here to see AI-generated examples of implementing the solution.

Bibliography

Baxter, S., Johnson, M., Chambers, D., Sutton, A., Goyder, E. & Booth, A. (2019) Towards greater understanding of implementation during systematic reviews of complex healthcare interventions: the framework for implementation transferability applicability reporting (FITAR). BMC Medical Research Methodology (2019) 19:80.

Bierman, AS. & Mistry, KB. (2019) Commentary: Achieving Health Equity - The Role of Learning Health Systems. Health Policy. 2023 Nov;19(2):21-27. doi: 10.12927/hcpol.2023.27236.

Bongaarts, J. (2009) Human population growth and the demographic transition. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009 Oct 27;364(1532):2985-90. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0137

Boustani, M., Alder, CA & Solid, CA (2018) Agile Implementation: A Blueprint for Implementing Evidence-Based Healthcare Solutions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018 Jul;66(7):1372-1376. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15283.

Cambon, L., Minary, L., Ridde, V. & Francois, A. (2013) A tool to analyze the transferability of health promotion interventions. BMC Public Health 13, 1184 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1184

Cozza, M. & Gherardi, S. (2023) Introduction: The Posthumanist Epistemology of Practice Theory. In: Cozza, M., Gherardi, S. (eds) The Posthumanist Epistemology of Practice Theory. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-42276-8_1

European Commission (2017) Tools and methodologies to assess integrated care in Europe. Report by Expert Group on health Systems Performance Assessment. European Commission, Luxemburg. 13.4.2017.

European Union (2019) Ageing Europe Looking at the lives of older people in the EU. Statistical books, Eurostat, 2019 edition, European Union.

Fakhruddin, B., Torres, J., Petrenj, B. & Tilley, L. (2020) ‘Transferability of knowledge and innovation across the world’. In: Casajus Valles, A., Marin Ferrer, M., Poljanšek, K., Clark, I. (eds.), Science for Disaster Risk Management 2020: acting today, protecting tomorrow, EUR 30183 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2020, ISBN 978-92-76-18182-8, doi:10.2760/571085, JRC114026:https://drmkc.jrc.ec.europa.eu/portals/0/Knowledge/ScienceforDRM2020/Files/ch05.pdf

Gherardi, S (2018) Practices and knowledges. Teoria e Prática em Administração 8(2):33-59. DOI: 10.21714/2238-104X2018v8i2S-38857.

Gherardi, S. (2019) Practice as a collective and knowledgeable doing. Siegen: Universität Siegen: SFB 1187 Medien der Kooperation 2019 (SFB 1187 Medien der Kooperation – Working Paper Series 8). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12641.

Koivisto, J. & Pohjola, P. (2011) Practices, modifications and generativity – REA: a practical tool for managing the innovation processes of practices. Systems, Signs & Actions. An International Journal on Communication, Information Technology and Work, Vol. 5(1), 100–116.

Koivisto, J. & Pohjola, P. (2015) Doing together: Co-designing the socio-materiality of services in public sector. International Journal of Actor-Network Theory and Technological Innovation (IJANTTI). Vol 7(3), 1-14.

Koivisto, J., Pohjola, P. & Pitkänen, N. (2015) Systemic innovation model translated into public sector innovation practice. The Public Sector Innovation Journal, 20(1), 2015, article 6.

Miettinen, R., Samra-Fredericks, D. & Yanow, D (2009) Re-Turn to Practice. An Introductory Essay. Organization Studies, 30: 12, 1309-1327.

Moore, G., Campbell, M., Copeland, L., Craig, P., Movsisyan, A., Hoddinott, P., Littlecott, H., O’Cathain, A., Pfadenhauer, L., Rehfuess, E., Segrott, J., Hawe, P., Kee, F., Couturiaux, D. & Hallingberg, B. (2021) Adapting interventions to new contexts—the ADAPT guidance. BMJ 2021 374(1679). doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1679

Moullin, JC., Sabater-Hernández, D., Fernandez-Llimos, F. & Benrimoj, SI. (2015) A systematic review of implementation frameworks of innovations in healthcare and resulting generic implementation framework. Health Research Policy and Systems (2015) 13:16: DOI 10.1186/s12961-015-0005-z

Nilsen, P. & Bernhardsson, S. (2019) Context matters in implementation science: a scoping review of determinant frameworks that describe contextual determinants for implementation outcomes. BMC Health Serv Res 19, 189 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4015-3

Nilsen, P. (2015) Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks Implementation Science volume 10, Article number: 53 (2015) https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0

Nolte, E. & Groenewegen, P. (2021) How can we transfer service and policy innovations between health systems? Policy Brief 40. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1350707/retrieve

Nuño-Solinis, R. & Stein, V. (2015) Measuring Integrated Care – The Quest for Disentangling a Gordian Knot. Internationl Journal of Integrated Care, 15(3), 1-3.

OECD/European Union (2020), Health at a Glance: Europe 2020: State of Health in the EU Cycle, OECD Publishing, Paris. doi.org/10.1787/82129230-en.

Omran, AR. (2005) The epidemiologic transition: a theory of the epidemiology of population change. 1971. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4):731-57. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00398.x. PMID: 16279965; PMCID: PMC2690264.

Powell, BJ., McMillen, JC., Proctor, EK., Carpenter, CR., Griffey, RT., Bunger, AC. Glass, JE. & York, JL. (2012) A Compilation of Strategies for Implementing Clinical Innovations in Health and Mental Health. Medical Care Research and Review 2012 APR;69(2):123-157. doi: 10.1177/1077558711430690.

Scarbrough, H. & Kyratsis,Y (2022) From spreading to embedding innovation in health care: Implications for theory and practice, Health Care Manage Rev. 2022 Jul-Sep;47(3):236-244. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000323.

Schloemer, T., & Schröder-Bäck, P. (2018) Criteria for evaluating transferability of health interventions: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. Implementation Sci 13, 88 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0751-8.

Skivington, K., Matthews, L., Simpson, SA., Craig, P., Baird, J., Blazeby, JM. et al. (2021) A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance BMJ 2021; 374 :n2061 doi:10.1136/bmj.n2061

THCS (2023) A scoping review on the methodological frameworks for supporting transferability and implementation of practices in the health and care systems. Publications of THCS Transforming Health and Care Systems Partnership, Additional Deliverable 4.2.1, 2023.

Wang, S., Moss, JR. & Hiller, JE. (2005) Applicability and transferability of interventions in evidence-based public health. Health Promot Int. 2006 Mar;21(1):76-83. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dai025. Epub 2005 Oct 25. PMID: 16249192.

Villeval, M., Bidault, E., Shoveller, J. et al. (2016) Enabling the transferability of complex interventions: exploring the combination of an intervention’s key functions and implementation. Int J Public Health 61, 1031–1038 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-016-0809-9

Wiltsey Stirman, S., Baumann, A.A. & Miller, C.J. (2019) The FRAME: an expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implementation Sci 14, 58 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0898-y